One of the common challenges that EFL teachers face is teaching students to use auxiliary verbs in questions.

This is a conundrum that I didn’t have to deal with when teaching Spanish and German to high school students in California and New Jersey prior to moving to Chile. With the exception of haben in German, neither Spanish nor German have auxiliary verbs that are used in the same way as in English (with the exception of the verb to be). This made my life as a language teacher relatively easy in that sense, as I very rarely came across a student that tried to translate the auxiliary verb of do or does into Spanish or German when forming a question.

I remember struggling to teach students to use do and does in questions when I had my first beginners back in 2010. I really focused on the rule and form, and I had difficulty helping students see when they had to use do and does in contrast with is , are, or am.

After contemplation and comparing English with Spanish over the years, I now walk my students through some different activities that help the concept of auxiliary verbs stick. They have to do with the use of auxiliary verbs in English versus Spanish, yes/no questions, information questions, and using manipulatives to reinforce sentences and questions.

Part 1: The use of auxiliary verbs in English versus Spanish

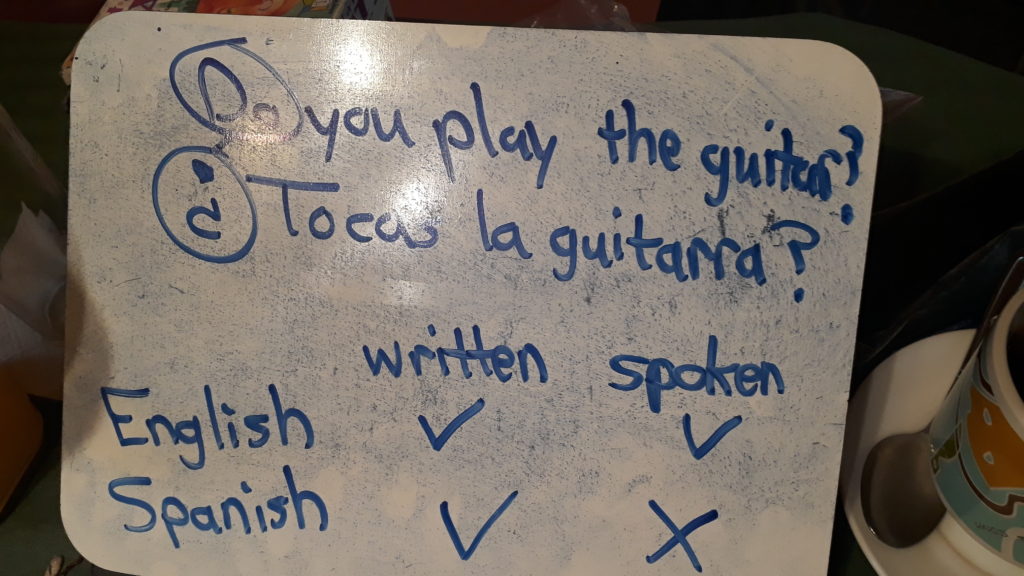

First, I write the following two questions on a whiteboard:

Do you play the guitar?

Tocas la guitarra?

I then ask if the question in Spanish is written correctly. Most students say yes, but I point something out to them:

¿ is missing from the beginning of the question. It should be:

¿Tocas la guitarra?

I acknowledge the argument that we are in the year 2019, and due to technology that the use of ¿ is becoming less and less common. While that is true, if we consider grammatically correct Spanish, the use of ¿ is necessary.

We then look at how we mark for questions in English and Spanish.

In both languages, we have a written indicator of a question. In English, it’s the auxiliary verb (in the present simple, do or does). In Spanish, it’s the upside-down question mark.

The difference occurs when we consider indicating questions in spoken language. In English, we say the auxiliary verb (again, do or does in the present simple). In Spanish, however, there is no word indicating a question. The only way you can tell it’s a question is based on a speaker’s intonation.

Here’s a summary of what I used to explain this to a beginner student a few months ago:

Part 2: Yes/No questions

I then progress to asking my students yes/no questions. For example:

Do you eat chocolate?

Do you swim in the ocean?

Do you have any brothers or sisters?

Their possible answers are as follows:

Yes, I do. No, I don’t. Sometimes. It depends.

Once we go through some questions, I then let them ask me some yes/no questions. By this point, my students already have a good amount of vocabulary, so they should be able to form questions with minimal help. (If you are teaching teenagers, their questions might become a bit scandalous, so you will have to set appropriate expectations here!)

I can turn this into a game with the students having to ask me questions to which I respond, Yes, I do. For a small-group class, students ask me one question at a time, and the first student to get 5 yes answers wins. For larger or individual classes this won’t work in the same way, but you can provide practice in other ways.

Part 3: Information Questions

Depending on the students’ level and time constraints, I could then move onto adding in question words to create more open questions. (To make the language user-friendly, I call these questions information questions.)

I ask students if they know any question words, and I usually find that they know at least a few. I write them on the board and add in any that they didn’t say. This usually looks like this:

Who

What

When

Where

Why

How

How much

How many

How often

Which

I write these words along the left side of the board on purpose, as it then allows me to add do and does to the right. From there learners can see that the word order of questions remains the same; question words are simply added before the auxiliary verb.

We could practice with writing questions on individual whiteboards, making sure that do or does appear after the question word and before the subject. Some questions that we might formulate together are as follows:

Where do you live?

How do you go to work?

When do you wake up in the morning?

How many times do you check your email a day?

If I were working with a small-group class, after working together I might ask each student to formulate three to four questions to ask another student. Once I check for accuracy, they could ask a partner and record their answers. Afterwards, they could switch partners and record the new answers. I could then finish the activity by asking them to tell me one thing about each other student in the class. By doing this, I can check that they are using the third person singular correctly. (I haven’t taught this to a small group of students in more than 3 years, so I don’t have anything formally prepared that I can share. Most of my classes are with individuals, but this gives you an idea of what is possible.)

Part 4: Using manipulatives to reinforce sentences and questions

Depending on your students, they might need more practice with questions to remember the correct word order and the auxiliary verb. By adding an element of kinesthetic learning and color, we can review word order in sentences and see the relationship between sentences and questions.

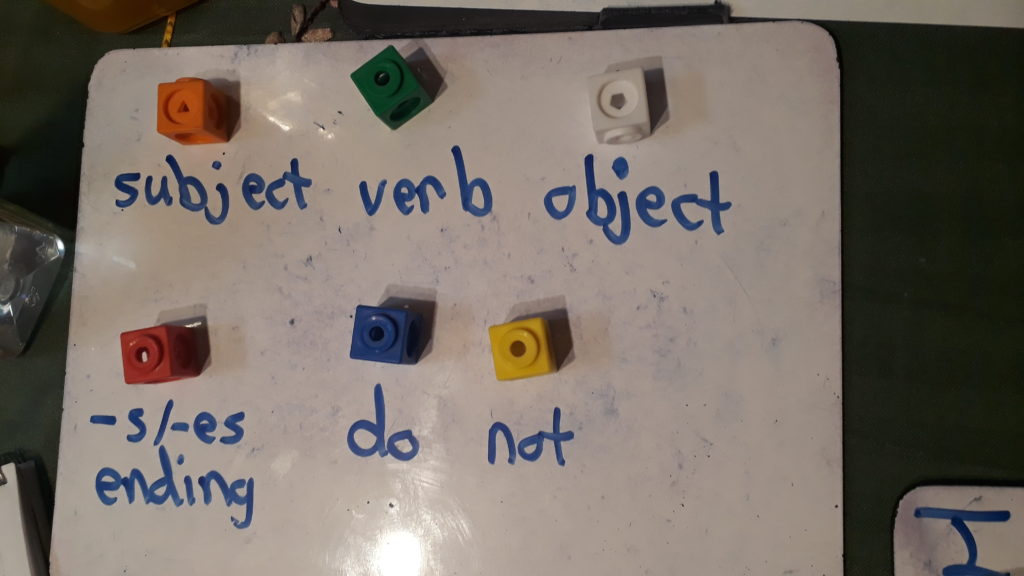

When I taught kindergarten, we used plastic blocks that snapped together to teach colors and patterns. I took this element to apply to parts of a sentence (subject, verb, object) and other important elements (third person “s” or “es”, “do”, and “not”). I let my students decide which color would represent each of these. Here is what one student decided:

I then told the student a sentence, and he had to formulate the sentence using the correct blocks. After that I said a sentence using the third person, and he had to make the necessary changes. We then converted the sentences to questions. Here is what it looked like with the blocks:

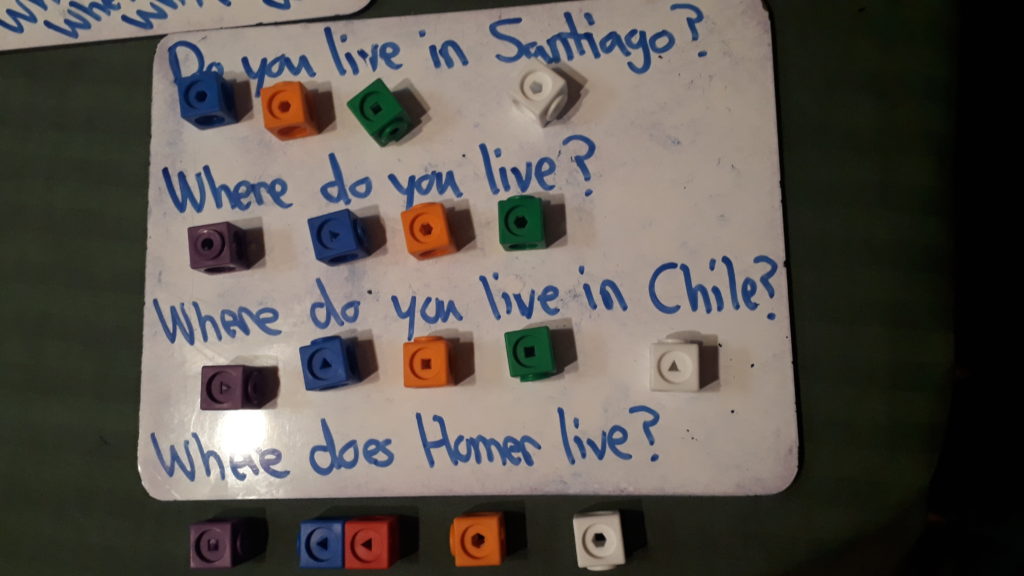

We then added in the element of a question word to move beyond yes/no questions. Here are what the boards looked like:

In Conclusion

These are a variety of activities that have proven successful for me working in the context of teaching Chilean students as individuals or in small groups. Depending on the pace of your students and time constraints, these activities can be shortened or expanded to meet your students’ needs.

A key consideration is to keep your students engaged and to get them curious and thinking about language; if we don’t push them beyond their comfort zone it’s not likely that they will grow into confident autonomous learners.

Last but not least, language acquisition isn’t always as straightforward as we would like it to be. We can’t expect students to master the use of the auxiliary verb within a period of one class or a series of classes. By laying the groundwork and giving the students a solid understanding and hands-on practice with how questions work, however, we are setting them up for success for their future learning.

4 Responses

Great article with great tips Daniel. Especially using the coloured blocks. I have a question. How do you go about teaching questions that don’t use auxiliary verbs? Eg. Are you hungry? Is he tall? Where is the bathroom?

Then there is the auxiliary “have”. Eg. Have you seen this movie?

Do you have a specific strategy for those situations?

Thanks!

Hi James, thanks for your comment!

In the examples you mention, the verb “to be” functions as the auxiliary verb; it doesn’t have a main verb like the rest of the present simple. As for “have” as an auxiliary verb, for the present perfect “have” or “has” function as the auxiliary verb. It is used in conjunction with the past participle to form the present perfect.

As for strategies, I would use the same colored blocks. I would contrast the questions with “do/does” with questions with “to be” and let students see the difference. With the present perfect, you can show the contrast between “do/does” and “have/has” and the base form of the verb versus the past participle.

I hope those tips help!

I love the idea of ¿ representing ‘do’. Thank you Daniel.

Thanks for letting me know Lesley!